“The Death’s Door name derives from an ancient Indian legend.”

“The Death’s Door name derives from an ancient Indian legend.”

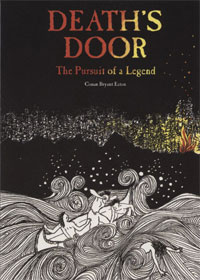

Title: Death’s Door: The Pursuit of a Legend

Author: Conan Bryant Eaton

Publisher: Jackson Harbor Press (1996)

ISBN 0-9640210-7-2

Softcover: 53 pages

Where to buy: Books Up The Road, Islandtime Books and More, Amazon.com

Book Excerpt, Death’s Door: The Pursuit of a Legend:

Legends of Michigan and the Old North West confesses that its stories about Indians are “gleaned among the uncertain, misty line, dividing traditional from historic times.” This is the misty line we must approach if we hope to find the beginnings of a legend which has surely been told for one hundred fifty years and perhaps much longer.

The Death’s Door name derives, we are often told, from an ancient Indian legend. This we may at least tentatively accept, considering the testimony of many years and the definition of “legend” as “any story coming down from the past, especially one popularly taken as historical though not verifiable.” Surely, it seems possible that Indians of this region may have passed the germ of today’s Death’s Door legend from one generation to another, for we know that “our Wisconsin tribesmen had stories, myths, and legends about many of the springs, streams, lakes, prairies, woodlands, rocks, hills, and valleys of the regions, which were theirs. . . . In the centuries of their occupation of their homeland, as a result of their life experiences and culture, a wealth of tales and legends became attached to many of the scenic landmarks of their environment.”

But we should be cautious in accepting these tales as history, for “the Indians have a peculiar habit of ‘continued stories,’ by which at the tepee fire one will take up some well-known tale and add to it and so make a new story of it, or at least a new conclusion. As with the minstrels and minnesingers of feudal Europe at the tournaments, the best fellow is the one tells the most thrilling tale.”

Lest we look too smugly at the “peculiar habits” of Indian storytellers, let us remember that it was certain European—not Indian—historians whom John Gilmary Shea called “that amiable class who seem to tell truth by accident and fiction by inclination.” We shall have the chance to judge many varying versions of the Death’s Door story; perhaps our judgment may gain charity if we consider these words from a United States Supreme Court decision:

“No human transactions are unaffected by time. Its influence is seen on all things subject to change. And this is peculiarly the case in regard to matters which rest in memory, and which consequently fade with the lapse of time, and fall with the lives of individuals.”

We deal here with a legend which demonstrably has endured at least a century and a half of telling and re-telling, twisting, shaping, augmenting and embroidering. We gather and examine the recountings of the past, and observe the remarkable workings of human purpose and human memory in transmitting the story of what may have been, at some precise point in history, a very simple occurrence. Finally, we search for the truth about that occurrence.

Conan Bryant Eaton

Wholly apart from the legend, the straight has earned a legendary reputation. The very name of the passage seems to make events near it more newsworthy, seems to invite overstatement. Thus, occasional writers cannot resist the temptation to sink La Salle’s Griffin in Death’s Door, improbable as that fate may be. There is no doubt that September of 1679 saw the first well-recorded crossing in a storm of a turbulent straight. The Griffin had sailed, the Recollect friar Hennepin tells us, from the “Island just at the Mouth of the Bay,” and a day later LaSalle’s party of fourteen departed in:

“. . . four Canoùs, laden with a Smith’s Forge, and Instruments, and Tools for Carpenters, Joyners, and Sawyers, besides our Goods and Arms. We steer’d to the South toward the Continent . . . about the middle of the way, in the Night-time, we were surpriz’d with a sudden Storm, whereby we were in great danger. The waves came into our Canoùs; and the night was so dark, that we had much ado to keep company together; However, we got shoar the next day.”

The dangers besetting La Salle have not lessened in three hundred years. Two official sources describe them this way:

“Porte des Morts (Death’s Door) passage. This is a strong current setting in or out according to the direction of the wind, and many vessels have been lost in consequence; it is frequently so strong that sailing vessels cannot make headway against it. The coast is rock bound and certain destruction awaits the craft going ashore. Sometimes the current is against the wind.”

“Porte des Morts Passage, Wisconsin, is known as ‘Death’s Door,’ owing to the numerous detached reefs and shoals obstructing its navigation . . . almost certain destruction to craft going ashore. These conditions have been the cause of many vessel disasters.”

Any list of losses in and around Death’s Door rings with a mournful music like bellbuoys near fog-shrouded shoals. Our search for the legend will make us witnesses to some events in the passage, but there are many thrilling stories which have no connection with the legend:

“In November 1853, in an old lumber brig . . . We left Chicago, under full sail with a brisk south wind, and early the second night out, were at Port Du Mort or Death’s Door. In the act of coming up to the wind to enter the Door, we were met by a gale of wind from the northwest. The old brig failed to come in stays and the captain was obliged to wear ship, and in doing so, we passed out within twenty-five feet of the Door Bluffs, reaching the open lake where we scudded under bare poles until we were abreast of Milwaukee when the wind abated sufficiently to enable the Captain to again make sail and head her again for Green Bay.”

The Fredericksons of Frankfort, Michigan, raised in the atmosphere of Great Lakes navigation, recount:

“On September 16, 1888, the heavily laden schooner Fleetwing was making ready for another trip. Dusk was approaching . . . her sails were set for the trip across the bay with an increasing westerly wind, she made good way. The captain shaped his course and hoped for a fast trip through the dreaded Death’s Door Passage and on into the waters of the big lake. In the early days of sail, it required a lot of luck and first class seamanship to make the passage after dark or in periods of poor visibility. The Fleetwing soon fetched the dark shadows of the high land close aboard her starboard bow. In the darkness, the captain mistakenly took Death’s Door Bluff for Table Bluff and dropped her off to the eastward for a passage through the narrows of the Door. After running a short time on this heading, the captain became alarmed at seeing no welcoming loom of an opening in the darkness or the lights of Plum and Pilot Islands up ahead and ordered the helm ‘hard down’ and commanded the watch to ‘about ship’ . . . She ran out of sea room and fetched up standing, with a terrible splintering crash, on the rocky beach. When the storm was over, the ship had almost gone to pieces where she lay.”

Even when used in a humorous account, the Death’s Door name retains its character as a symbol of marine oblivion. A 1961 history suggests that, had certain Milwaukeeans known the problems involved when they purloined a steamboat from Buffalo, “They might have left her in the Porte du Morte.”

A Pictorial Marine History, published in Sturgeon Bay, tells us:

“A diary of the lighthouse keeper of Plum Island, kept from 1972 to 1889, indicates that winds and roaring seas with a shipwreck at least twice a week was the usual course of things. In the fall of 1872, eight large vessels stranded or shipwrecked in Death’s Door . . . in one week in 1872, almost a hundred vessels were lost or seriously damaged passing through the Door. The worse storm that ever occurred on Lake Michigan up to 1880 came out of the south on October 15 of that year [the Alpena Gale]. In the vicinity of Plum Island, in Death’s Door, there was a neighborhood of thirty vessels driven ashore.

“The schooner Resumption was one of the few large sailing vessels on the great Lakes in the nineteen hundreds, fond its final resting place November 7, 1914, on Plum Island, Death’s Door Passage . . . bound from Chicago to Wells, Michigan, in light trim, with a heavy gale blowing from the southwest. On reaching the Door, she attempted to come about when abreast of Plum Island, but missed stays and before the anchor could be lowered, she had been carried up on the beach by the wind and sea . She was abandoned as a total wreck.”

This shipwreck is a boyhood memory of Washington Island’s Milton Cornell, whose father was first assistant lighthouse keeper on Pilot at the time. “We watched her from the tower,” says Milton, “and went aboard the next day.” He recalls the crew’s hands burned from letting down the sails so fast in the emergency.